Silencing the Generalizations of the Liberal Arts

January 11, 2016

When Scotty Striegel first started college, he planned to major in civil engineering. He thought the field provided good job prospects. But while studying at Ivy Tech in 2011, he quickly learned that he had a fondness for classes that focused on writing and literature.

Now a junior at IU Southeast, Striegel in majoring in English, with a focus in writing. He says this choice will give him a “more enjoyable college experience and hopefully a more personally rewarding job in the future.”

But while he’s confident in his choice, that doesn’t mean he doesn’t get flak from his friends and family for choosing English as a major.

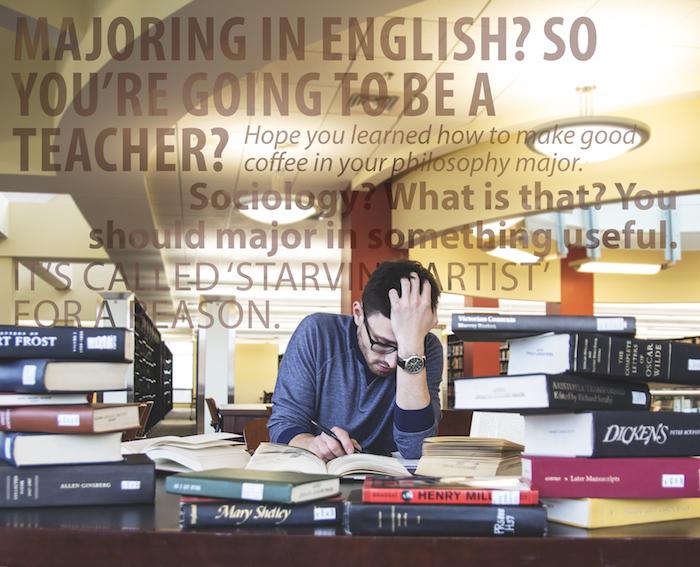

“I’ve heard all the usual tropes from people regarding my degree,” Striegel said. “Things like, ’What are you going to do with that?’,’Why would you want to write that much?’,’So, you’re a liberal, huh?’ Goofy stuff like that.”

Students majoring in subjects like English, foreign language, philosophy, music, fine arts, psychology, sociology, and history might hear similar message. Clichés suggesting unemployment, evoking images of the “philosophical barista” or the “starving artist,” are all too common. It’s a message that is even prominent in national presidential politics.

In November 2015 during a Republican presidential primary debate, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-FL, said, “Welders make more money than philosophers. We need more welders and less philosophers.”

Some saw problems with this statement. First, the wage difference between welders and philosophers is inverted. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, philosophers actually make a mean salary of $70,000, nearly double the $40,000 mean salary of a welder.

But more importantly, some say, these kinds of statements ignore the broader value of an education as well as the broader occupational skills that students in so-called “liberal arts” majors gain.

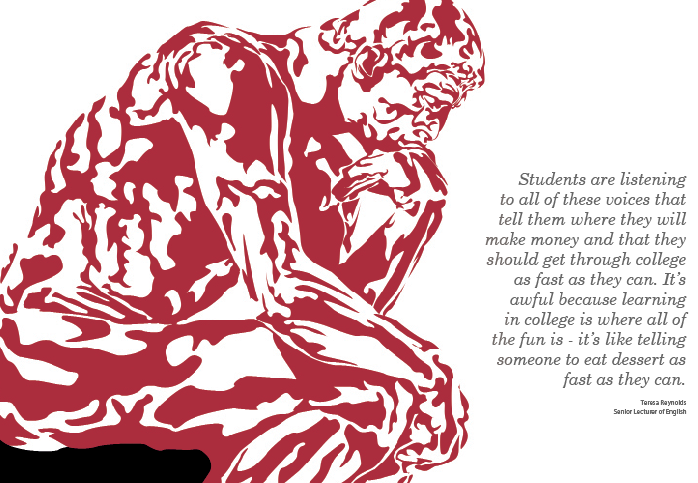

Teresa Reynolds, senior lecturer of English, said students are being told to abandon their passions and instead focus on vocationally oriented degrees.

“Students are listening to all of these voices that tell them where they will make money and that they should get through college as fast as they can,” Reynolds said. “It’s awful because learning in college is where all of the fun is – it’s like telling someone to eat dessert as fast as they can.”

Reynolds said she believes that for a while now, people have viewed college as the necessary next step for a career, one of many stepping stones on the way to concrete employment. What she finds disheartening is that most have forgotten just how special education is.

“It’s awful. I wish students would understand that education is sacred; it’s a gift,” Reynolds said. “If students would come to school with an excitement for what they are going to learn that day and try to find themselves, it would be so much fun for them, and they wouldn’t have trouble finding what they love.”

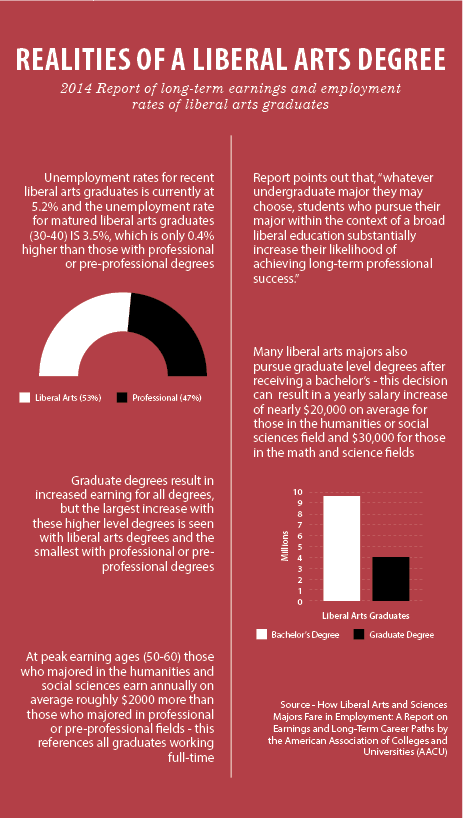

But even for the pragmatist, laser-focused on achieving a degree as a gateway to a career, liberal arts may be more lucrative than some may think.

According to a 2009 report by the American Association for Colleges and Universities, over 75 percent of the nation’s employers strongly recommended that college-bound students pursue a degree in the liberal arts, with 89 percent of those employers looking for students with an emphasis in both reading and writing.

Jennifer Myers is an academic adviser in the School of Arts and Letters, home to many liberal arts majors. She said when she hears students and parents express concern about the employability of liberal arts majors, she tells them how through those majors they’ll learn skills broadly applicable to potential careers.

“The liberal arts really allow students to experience a broad range of subjects, and it really opens up the minds of students,” Myers said. “It teaches students how to become critical thinkers.”

She said that often employers are not concerned that employees can perform a specific task – something they can train to do in the workplace – but rather they want employees to excel in the broader skills that are difficult to teach on the job.

“For the most part, an employer is going to teach employees the basic skills that are needed to do the tasks for a job,” she said. “He or she is not going to take the time to teach the necessary things like speaking well, writing well, working well with others, thinking analytically.”

One of the essential skills employers look for is the ability of written and oral communication, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). The organization found that the skills employers were most interested in were critical thinking, problem solving, teamwork, professionalism, and oral and written communication.

Reynolds said she sees critical thinking as especially valuable.

“Critical thinking means that you can look at a situation and know what tools you have and know how to use them, and they might not be the same tools that you used yesterday for a different problem,” she said. “It’s about learning constantly, and that’s what liberal arts majors are so good at – learning how to learn.”

Myers said that employers are interested in an employee’s communication and critical thinking skills because these two elements are integral parts of any organization. Without employees who can approach problems from an analytical and critical perspective, she said businesses are likely to struggle.

“Somebody might ask, ‘Why do I need to take philosophy?’ Well, why not? It allows you the ability to break down and analyze things, to think about things critically and look at them from different viewpoints,” Myers said. “These are the values of the array of courses that the liberal arts requires of students.”

Employers and educators are not the only ones who are touting the value of liberal arts.

As U.S. educational policy has trended toward professional degrees, other countries have started to put increased focus on liberal arts education. For example, the Chronicle of Higher Education reported that educators and administrators in countries like China, Japan, South Korea and Singapore are beginning to shift their focus to a more critical thinking- and creativity-related curriculum.

In 2012, China opened Xing Wei College, its very first modeled after the idea of a western liberal arts institution. The private three-year institution opened with the goal of providing students with more cognitively complex critical thinking skills.

Myers says the conflict between the arts and more professional or scientific degrees isn’t necessary, that they all complement one another.

While the predominant focus in U.S. education has been on STEM — science, technology, engineering and math — a recent trend has emerged to add arts into the mix, labeled STEAM.

“I think that there is definitely a need for technical education because we certainly need people with these skills and traits,” said Myers. “For years the pendulum swung towards everybody needing a more professional education and perhaps it is beginning to even out a bit.”

While the stigma between the two variations of education is beginning to decrease, there are still some skeptical of the liberal arts.

Striegel said that, while the usefulness of liberal arts graduates in the workforce may not be immediately apparent to most, this lack of awareness doesn’t negate the impact that liberal arts majors can have in the modern workplace.

“Sure, we’re not crunching numbers or predicting weather patterns, but people forget how important people from liberal arts backgrounds are. We’re the people that keep them informed through all manner of the texts and works we produce,” Striegel said.