As a personal counselor at IU Southeast, Kelley Quirk meets many students in need of help. Some come to her with grade worries and need help getting A’s and B’s.

As a personal counselor at IU Southeast, Kelley Quirk meets many students in need of help. Some come to her with grade worries and need help getting A’s and B’s.

Others, however, have a harder time getting Z’s.

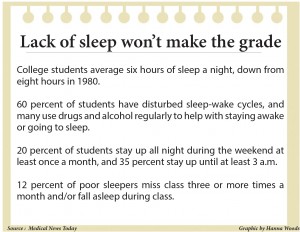

Sleep deprivation is a common concern among college students, Quirk said. She said that it is a troublesome issue on its own, as well as a potential indicator of more serious problems.

“For some people, anxiety is the issue, and they’re kept awake by ruminating, repetitive thoughts,” Quirk said. “The other population we see a lot are people who can’t sleep because of their depression.”

Numerous factors can cause it, Quirk said. Studies have shown that sleep deprivation can have a variety of negative effects.

According to a 2007 study conducted by St. Lawrence University, two-thirds of surveyed students pulled at least one all-nighter during a semester, and students who frequently did had lower GPAs on average. Similar studies have also found that students who lack sleep can experience a bevy of emotional and health-related issues.

As these side effects have become widely known, sleep deprivation has become a more serious issue to students. This has led some of them to take action and do research – and colleges are beginning to step in as well.

While sleep deprivation is a problem for all demographics, research has often suggested that it is particularly common among college students. In a recent study by the National Sleep Foundation, it was estimated that 63 percent of college students do not get enough sleep.

Some students prefer to spend their nights hanging with friends and partying instead of getting rest. Others find it tricky to balance work, school and sleep.

“I don’t get as much sleep as I should,” Cassie Nichols, nursing junior, said. “It’s tough when you’re a full-time student who also works. I know a lot of students who feel that way.”

In response, researchers have started to pay more attention to this issue. Studies on sleep deprivation are frequently published across the nation, and many harmful side effects have been documented.

Often, poor academic performance among sleep-deprived students is a main concern of these studies. According to a study published by the University of Minnesota, students’ GPA scores were shown to correlate with the average number of days a week in which students received more than five hours of sleep.

Researchers have also found lack of sleep can impair certain mental functions.

In an article published on Harvard University’s website, Dr. Lawrence Epstein, instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, said that sleep deprivation can result in “increased risk for developing emotional disorders, depression and anxiety.”

Sleep deprivation has been shown to reduce the effectiveness of the immune system, resulting in health concerns. Perhaps most notably, Linfield College said it can increase the risk of contracting meningitis – particularly for students living in residence halls.

Other effects observed by researchers include an increased risk of weight gain, frequent headaches and increased susceptibility to diabetes.

“Not getting enough sleep alters insulin resistance, which is associated with an increased risk of developing Type 2 diabetes,” Anne E. Rogers, faculty member of Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, stated in an article published by Harvard.

Some students have discovered methods that help them sleep.

“If I can’t sleep, I’ll try to do things that are relaxing instead,” Alexis Alexander, an art and psychology student, said. “I’ll read a book that I’ve read already or watch a movie I’ve seen already. It keeps your mind half busy while you try to sleep.”

Angelina Russell, biology freshman, said she takes a different approach.

“I listen to music and do a muscle relaxer technique that a therapist showed me a couple years back. Those normally do the trick,” Russell said. “And if those don’t work, I count sheep.”

Andrew Smith, English sophomore, said he has found that drinking milk has helped him sleep, noting that it appears to have “a psychosomatic effect.” He also said he sleeps best in cold temperatures.

“It has to be 60 or lower for me to sleep. I can’t sleep if it’s hot,” Smith said.

Quirk has also discovered some methods that help the students she counsels. She recommends setting aside a “worry time” in order to help students get their anxieties out.

“If you give yourself permission that ‘I’m going to worry about things’ from 5 p.m. to 6, it gives your brain relief before bed,” Quirk said. “I recommend it morning or midday. It’s not good to worry before bed.”

She also recommends exercise, as she has found that many of her students “are kept up by spare energy.”

Some colleges have even started to step in with their own potential solutions. University of Louisville started a new “flash nap” program this year, inspired by the popular trend of flash mobbing.

As part of the program, the students involved all take a break from their tasks and nap at the same time. The naps usually last from 20- to 40- minutes. IU Southeast teaches new students about sleep in its First Year Seminar course.

In this class – which is required by the university for freshmen – students are required to read IU Southeast’s College Success Guide, which discusses the concept of “sleep debt.” The book describes sleep debt as “accumulated sleep loss” and briefly details the negative effects it has on students, such as a decreased ability to pay attention or remember new information.

The majority of colleges, however, do not give students any information about sleep. According to the latest National College Health Assessment, only 24.6 percent of students have received sleep-related information from their universities.

The percentage of students satisfied with their sleep amount has remained similarly low. According to the same study, only 9.9 percent of surveyed students reported having “no problem at all” with daytime sleepiness. In addition, 41.8 percent identified themselves as having “more than a little problem” dealing with daytime drowsiness.

By NIC BRITTON

Staff

nmbritto@umail.iu.edu