Students learn from mock crime scene in Crestview Hall

Bernadette Jessie, social science professor designed this in a way that allowed for students to learn condensed versions of both forensic psychology and forensic science.

February 7, 2015

In the Crestview staff lunch area, a room that is blandly furnished for the sake of functionality with decorations that cater to the same level of excitement as the intended purpose of such a space, the body of a middle-aged man lies on the floor with the dark, but unmistakable hand of a knife crudely protruding from the mid-section of his back.

Behind him, thin streaks of crimson gild the otherwise blank wall and in a far off corner sits a puddle of vomit, its relevance to the scene likely to be significant, but yet to be determined.

At a quick glance it is clear that this room designated for staff lunches housed a struggle that at some point had turned maliciously violent, at least that is what Social Science professor Bernadette Jessie hoped for as she began staging the mock crime scene for her forensics class.

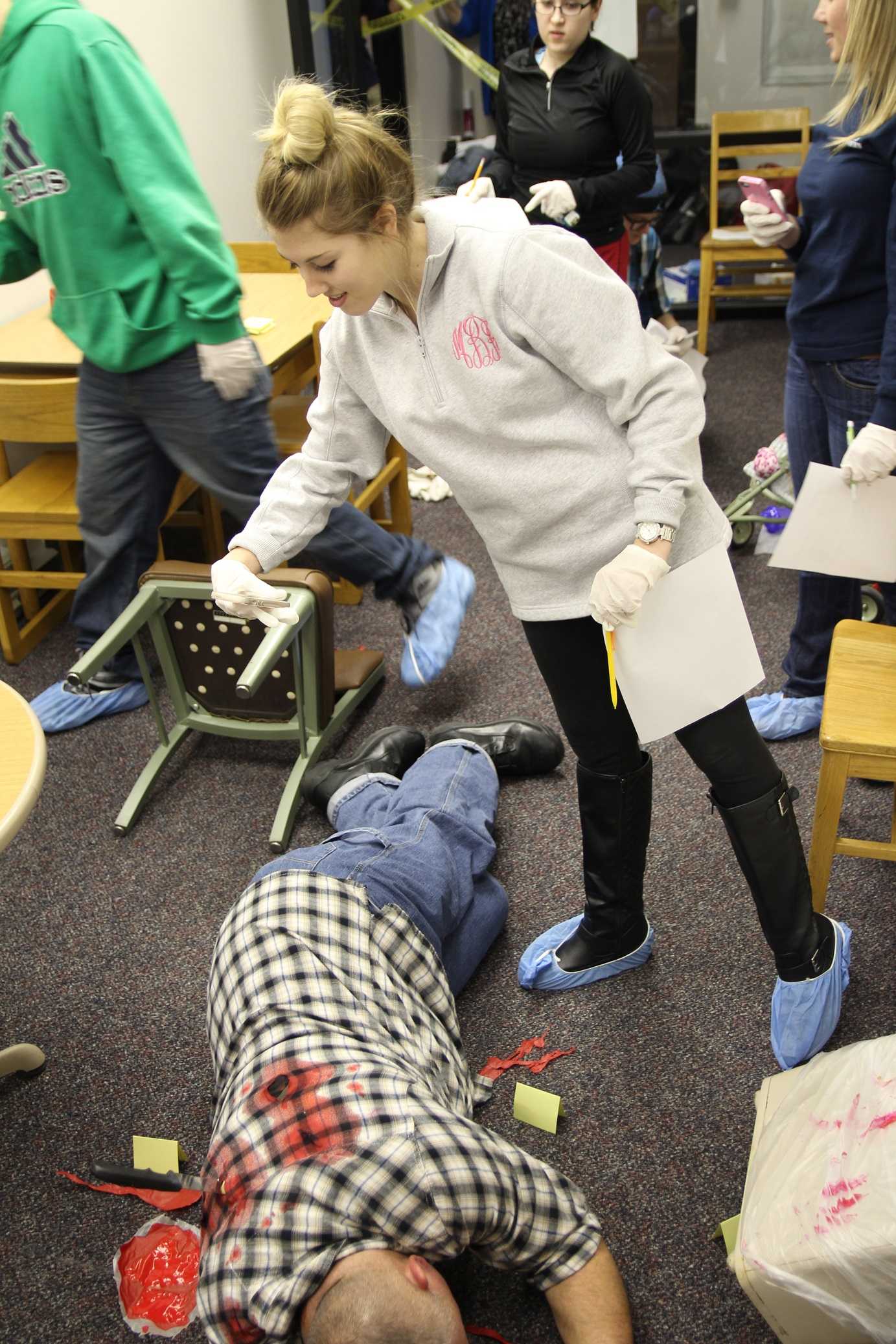

On January 29, groups of students huddled together in the cramped margins of the Crestview faculty break room, where they were instructed to approach the violent scene laid out before them as if the consistent trails of red on the walls were authentic and the lone puddle of vomit wasn’t store-bought.

Brittani Hatley, a criminal justice major, casually, yet cautiously shifts about the room, taking note of everything that is stumbled upon, aware that anything could be a significant piece of evidence in the unique exercise.

“The main reason that I enjoyed the assignment was that it showed me that I am in the right field and it really gave us a hands on look at being a first responder,” Hatley said.

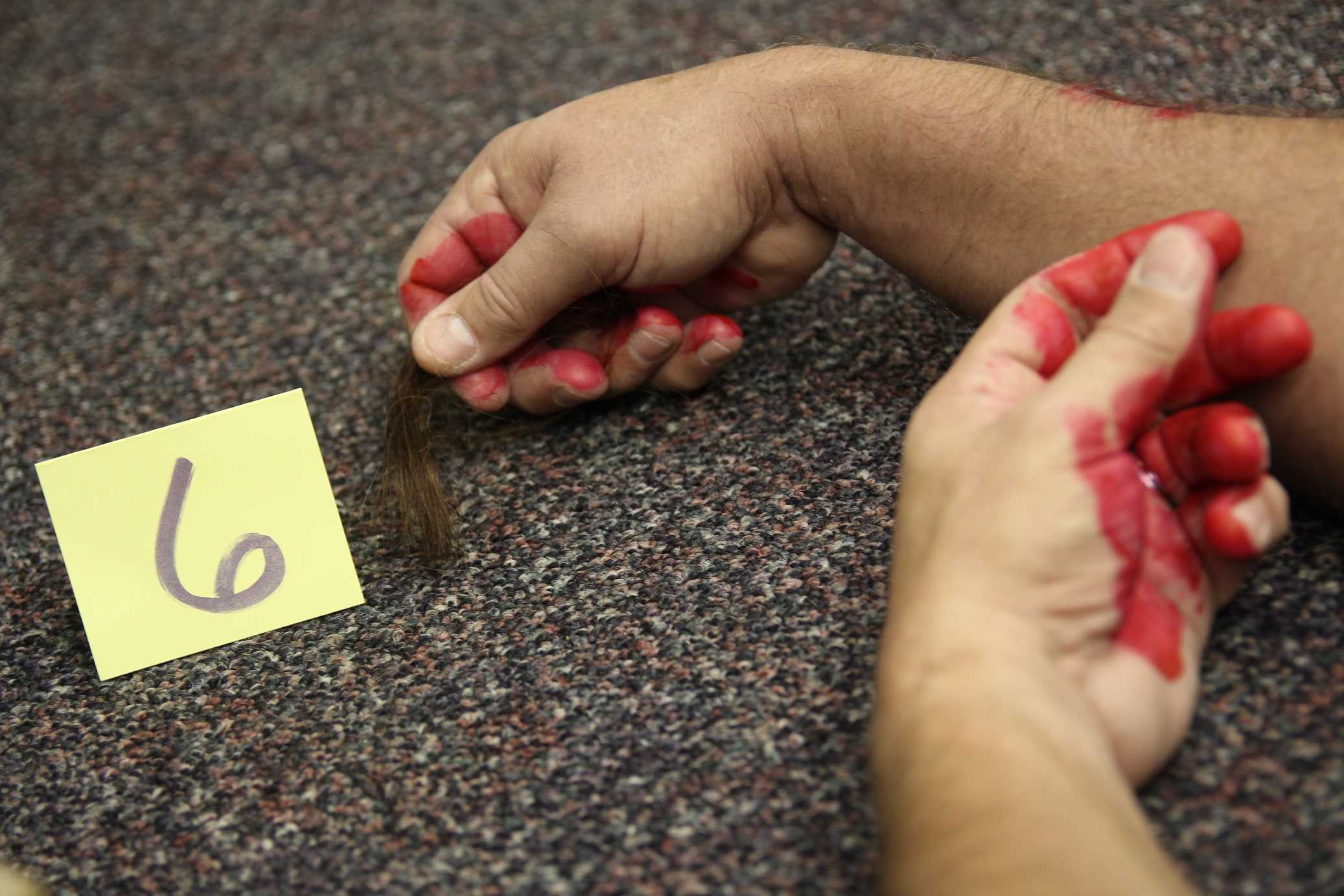

Through a paneled window, Jessie watches as her students begin carefully placing yellow evidence cards with gloved hands.

“In the past I’ve just done this in the classroom and we’ve not used a real body,” Jessie said, referring to her husband lying motionless as students continue inspecting the room.

While some facilities are better equipped to house a mock crime scene similar to the one that Jessie put together, she didn’t allow the department’s lack of resources hinder the learning outcome that she had hoped for when implementing some necessary creativity to the exercise, something that can be recognized in the faux mists of blood that she put together at home.

“I’m sure that my neighbors thought that I was crazy,” she said.

Due to the department being short-staffed and experiencing a deficit of resources, Jessie came up with the idea of designing the course a couple of years ago and constructed her lesson plan in a way that allowed for students to learn condensed versions of both forensic psychology and forensic science.

As the first group of students finished up their investigation, making sure that everything is as exactly as it were before entering then removing their gloves, Jessie smiles and watches them shuffle out of the room with the second group trails in, their interests clearly sparked upon seeing the sprays of crimson decorating the walls.

Some students immediately begin taking measurements of the room and begin sifting through what may or may not be evidence, each of them clearly interested in the exercise that Jessie has put together.

“Students love sexy stuff,” she points out.