Elizabeth Gritter: Beyond the movement

History professor and civil rights expert shares her story of digging into the historical and social aspects of the civil rights movement

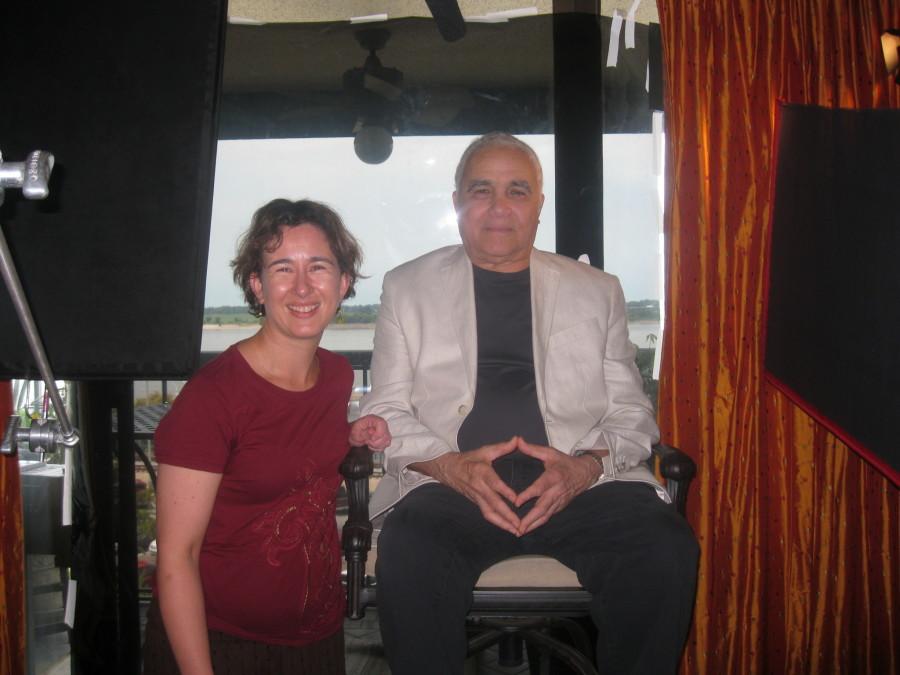

Gritter with Russell Bertram Sugarmon Jr, the first African American in Memphis to run for a major city office.

February 23, 2015

African-American History Month is an opportunity to turn our attention back to the past. It’s a time to remember the Civil Rights Movement, what it fought for and the people who fought. Much of this historical memory is shaped and amplified by those who investigate, record and teach that history.

Elizabeth Gritter has taught history at IU Southeast for the last two years. She’s an expert on the Civil Rights Movement with a focus on the movement’s Memphis chapter. She has conducted over 30 oral histories and turned her senior thesis into a book. While many historians focus on the speeches and accomplishments of the Movement’s major figures, Gritter, a self-described “social historian”, amplifies the movement’s lesser-heard and underappreciated voices.

Gritter grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Rather than beach trips for summer vacation, her parents took her to historical sites. While some families were at Disney World, Gritter was exploring the boyhood homes of Benjamin Harrison and Abraham Lincoln and taking in the grandeur of Mount Rushmore. These trips fueled the spark within Gritter that bloomed into a fiery love of history.

“I was interested in baseball history,” said Gritter. “Of Jackie Robinson and the integration of the major leagues. So I think that was a reason I got into African-American history.”

Baseball and historical sites were not to be her only loves. As Gritter grew up, she began to focus herself on history and politics. These fields allowed her to investigate a broad swath of topics under the umbrella of a single academic field.

“[Those fields] covered the human experience in a very comprehensive way,” said Gritter. ” I like how the past can break us out of our current frames of reference and understanding.”

When she graduated high school, Gritter was accepted at American University. While Washington D.C. was far from Grand Rapids, she decided to make the jump in an attempt to broaden her horizons.

In her sophomore year, Gritter took a class on African-American history that would set the course of her future academic endeavors.

“It just opened my eyes,” said Gritter. “And I thought this is why things are the way that they are. I could see the direct result of that historical legacy and persisting discrimination in the world today.”

The class’s instructor was Julian Bond. In the 1960s, Bond helped create the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which would become a major organization over the course of the Civil Rights Movement. He was the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center and chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from 1998 to 2010.

“She seemed to me to be a fresh-faced, soft-spoken, young woman,” Bond said. “She was a good student, going far beyond the requirements on the syllabus. I wish I had dozens like her.”

The class had an immense impact on Gritter.

“I had no idea growing up in a white, conservative community all the atrocities that African-Americans had experienced,” said Gritter. “And I didn’t know all the forms of activism and organizations and people that were involved. So I became fascinated by the movement.”

Gritter would take more classes with Bond while at American University.

“She went to Memphis to interview civil rights leaders [for an oral histories course], something totally not called for in the class,” said Bond. “But it stood her in good stead when the visit and her study allowed her to expand her research.”

That expansion took the form of her senior thesis. A few years later, she would turn her interviews and research into a book, River of Hope: Black Politics and the Memphis Freedom Movement, 1865–1954.

Gritter would remain close with Bond over the years. In 2008, she joined up on a bus tour he led through historic Civil Rights locations such as Birmingham, Selma and Montgomery. To this day, she describes Bond as a “mentor.”

“I am tremendously flattered to hear this,” Bond said of the moniker. “And proud to know her.”

In 2000, Gritter received the Harry S. Truman Scholarship. The scholarship, awarded by the Harry S. Truman Foundation, is a nationwide grant given to college undergraduates who distinguish themselves as candidates for public service careers after graduation.

“[Elizabeth] Gritter met all of the standards and is among the very top of the Trumans selected in my days in terms of intellect, human decency and compassion,” said Louis Blair, executive secretary of the Harry S. Truman Foundation from 1989-2006. “She has focused her research on a tragic period in U.S. history and shown us some of its heroes through inspired research.”

After graduating, Gritter was one of four researchers contacted by the Library of Congress to run the Civil Rights Project. The project located and cataloged the location of interviews and oral histories of the Civil Rights Movement throughout the nation.

Gritter has conducted over 30 oral histories of her own. Her subjects include Bond, John L. Seigenthaler, H.T. Lockard, Tom Prewitt, Billy Barnes, Russell B. Sugarmon Jr, and Maxine Smith.

“I like getting firsthand accounts of history,” said Gritter. “Some historians don’t like that. They like studying dead people. Partially because dead people can’t argue or critique what the historian writes.”

Gritter says that a big part of what interests her about the history she studies are the local people. She loves discovering the stories of these “lesser-known heroes.”

“There’s so much emphasis on Dr. King and what gets under-recognized is all of the local people that were involved in the struggle,” Gritter said. “People like H.T. Lockard and Maxine Smith and Russell Sugarman Jr.”

Gritter says that Bond once reminded her that the Civil Rights Movement was made up of thousands of local movements and the idea that it was a single movement is a myth. It’s a sentiment she takes with her into the classroom.

“When students take my classes. I try to not just let them know about the big names in history, but also how national developments affected local people and how local people affected national developments,” said Gritter.

When asked, fellow professors had glowing things to say about their fellow teacher.

“She’s prolific in her research,” said Joe Wert, associate professor of political science and current dean of the School of Social Sciences. “And she’s a wonderful colleague.”

Another one of Gritter’s colleagues echoed Wert.

“She’s pleasant, hard working and very easy to get along with,” said Yu Shen, professor of history. “Very energetic. Very sincere.”

When asked if her race has ever come up in her research, Gritter took the question in stride as though it were one she had heard before.

“I can’t speak to what people say behind closed doors. But I always found the people I interviewed to be very supportive of my work,” Gritter said. “And very grateful that someone was taking the time to record their stories. It never seemed to matter to them that I was white.”

However, Gritter did recall a few instances in which small things had arisen. One of Gritter’s interview subjects once told Gritter she did not want Gritter writing on the tensions within the movement.

“I did feel as though that was someback because as a historian this is the sort of thing I’m supposed to be covering,” Gritter said.

Gritter also recalled speaking with a professor who felt uncomfortable with white historians writing about African-American history and making money off it. This professor saw it as another form of exploitation.

“I am very sensitive to those kind of concerns,” said Gritter. “But ultimately, I don’t believe in segregating the way we record our history.”

Gritter believes more people of non-African-American ethnicities should begin taking a greater interest in the deeper history of the Civil Rights Movement.

“Part of forming a more tolerant society is learning about the history of other groups,” Gritter said. “That’s a really important part of teaching history. And one of the reasons why I do it.”