Jean Abshire, associate professor of political science and international studies encourages sexual assault victims to seek counseling. “It’s not something they have to go through on their own,” Abshire said. “Reach out to others and build a support network. Don’t struggle through it by yourself, and if you can, prosecute.”

Sexual Assault: Broadening the Conversation

January 21, 2017

Last fall, Margot Morgan, an assistant professor of political science at IU Southeast, led a panel of sexual assault survivors called “It’s Not OK.”

“This is something we don’t talk about.” Morgan said. “Since it happens to so many people you’d think it would be something we talk about but victims of sexual assault are isolated. They feel like they are completely alone because nobody wants to talk about it.”

Morgan was joined by colleague Jean Abshire, an associate professor of political science and international studies, and Kristina Foster, elementary education junior. These women shared their stories because they want a broader conversation about sexual assault.

Jean Abshire – “Everyday” sexual assault: Non-consensual groping and grabbing

Abshire said minimizing any account of sexual assault has become a part of the issue.

It does not have to be full-on sexual penetration to be considered sexual assault. She said it does not have to go that far to leave a lasting imprint on someone. She called many of her encounters of sexual assault over the past four decades everyday sexual assault.

“I have been groped by complete strangers. I have been kissed against my will by complete strangers. I have been sexually harassed at my workplace,” Abshire said.

With many encounters over the years, Abshire said she has felt a wide variety of emotions.

“Shock is always there. I always feel like this should not be happening,” Abshire said. “Sometimes there is fear, sometimes alarm, sometimes fury, and typically at some point there is a sense of feeling very vulnerable.”

Abshire was in her late 30s visiting another country. While standing on subway platform, a man came at her and attempted to grab her breasts.

“I smacked his hands away, and he hit me back. We faced off on a subway platform, and I yelled at that point,” Abshire said. “Nobody did anything. So, the guy and I faced off. He did not back off despite being hit and even though I yelled.”

Abshire said she backed off and put some other people between them, but he wound up getting on the same subway car as her.

“I was debating about whether I should get off because if I stayed on, he was on, and I would be trapped in a subway car with him,” Abshire said. “If I got off, he might jump off at the last minute. Then I would be alone on an empty subway platform with this guy who just tried to grab me and hit me.”

The standoff occurred on the platform just outside of Abshire’s hotel. She said that it put a dark mark on the rest of her trip.

“You bet I was looking over my shoulder,” Abshire said. “I was on high alert anytime I walked near that subway station.”

Abshire said for years she had a mental block about returning to that country because of this experience.

What some might brush off as insignificant could be traumatic for another person. Abshire said unwanted touching is too common in society.

“That meets the legal definition of sexual assault, and it is not OK,” Abshire said.“I think we need to raise awareness of what sexual assault actually is, how it impacts people, and that it is absolutely happening to women that everyone knows.”

She said if we do not tell people what is happening to us, then they don’t know. If only a couple of bad people are sexually assaulting the occasional women, it becomes too easy to dismiss.

“It’s much more common than that,” Abshire said. “Too many women have had these experiences. Clearly there is a lot of people doing this stuff. It’s something we need to look at in our society and address.”

She said we need a broader conversation within society to address these issues because we have a rape culture.

“To do better, we have to confront it and talk about it and figure out how to move forward,” Abshire said.

Kristina Foster: The courage to speak out

“It’s not your fault no matter what. No matter where you were, no matter what you were doing or how much you drank. None of that matters. It is not your fault,” Foster said. “Even if you don’t have the support of your friends and family, you can talk to the people on campus. They are willing to support you.”

Foster was sexually assaulted at a party by a friend.

“When I realized what was happening, I instantly went into shock,” Foster said.

Foster said she woke up with him on top of her. She went into shock and tried to pretend like she was sleeping, hoping to deter him. It didn’t work, and he was hurting her so she rolled away from him.

She said she was very scared. She was afraid he was going to try it again or that he would hurt her in another way. She said she lied to him, that she needed some water, and rushed out of the room. She ran upstairs to the bathroom and locked herself in.

“I just broke down into tears. I went to the bathroom because that was the only place I knew in the house,” Foster said. “I was crying. I was desperate for help. I kept asking myself ‘Why? Why did this happen to me?’”

Foster said the only thing she could think to do was to text some friends she knew were at the party. One of her friends answered and told her where he was. She left the bathroom to find him.

“He reassured me that everything would be OK,” Foster said.

Foster said the next day her friend told her what happened to her was considered sexual assault.

“I felt ashamed. I felt guilty,” Foster said. “I just had this feeling that it was my fault.”

The thought of reporting it was frightening to her, she said. She was afraid other people would learn what happened. She didn’t want other people to know.

Foster said once the news got out, people on campus started to avoid her. Others accused her of doing it all for attention. She said this made her feel worse about herself. She was already blaming herself for what happened.

“It got to the point where I didn’t really want to eat anything and I didn’t really talk to anyone anymore on campus,” Foster said.

Friends and mentors told her to seek counseling. She resisted at first because she said she did not want anyone to know that she was going to counseling either. After weeks of putting it off and at the persistence of someone from the Personal Counseling office on campus, Foster relented.

“It helped a lot,” Foster said. “I tried avoiding the question as much as possible. Just being able to be somewhere safe, outside of the normal world, was what really helped me realize that what had happened was what happened and it was not my fault.”

In the beginning, coming forward and reporting the sexual assault, telling others about it, was one of the scariest things about the situation, Foster said. She wondered what her friends would think. She wondered if they would feel differently about her.

“I want people to know my story,” Foster said. “I want people to know that it’s happening, and it’s real, and that it’s OK to tell people.”

Foster said the more that the people who commit assault realize their victims will talk, the less likely they will be to do it. She said she feels they do it because they think they can get away with it. They bank on their victims not having the courage or power to speak up.

“Knowing that they think that makes me mad,” Foster said. “We do have the power…the more we step up, the more predators will step down.”

Margot Morgan, associate professor of political science offers words of encouragement to sexual assault victims. “Love yourself,” Morgan said. “Don’t judge yourself. Don’t blame yourself. Don’t listen to people who try to put you down. Trust yourself. You know what happened. You know who you are. You know the truth.”

Margot Morgan: It can happen to anyone.

While in graduate school Morgan attended a party and had too much to drink. She fell asleep near one of her closest male friends.

“I woke up with his fingers inside me, and I froze,” Morgan said. “We talk about fight or flight, how those are the two animalistic responses, but there’s a third one, and it’s freeze. I think that’s what happens to a lot of victims. I didn’t just pop up and run away, and I didn’t punch him in the face. I froze. I couldn’t move.”

Morgan said she laid as still as possible, hoping he would think she was asleep and realize she did not want it to happen. When that failed to deter him, she pushed his hand away. When he tried again, she got up went to the bathroom and locked the door.

“I was so horrified, and I felt so alone, terrified and small that all I knew was I needed to get out of the house,” Morgan said.

She said she knew she was too drunk to drive and she couldn’t think clearly enough to call someone for help. She got up to leave, and he walked her to the porch.

She said her intention was to sit in the car for a while to clear her head. But he just stood there on the porch, staring at her. She had to get out of there, so she drove herself home.

“I was pretty lucky I did not kill myself or somebody else on the way home, but I had to get away,” Morgan said.

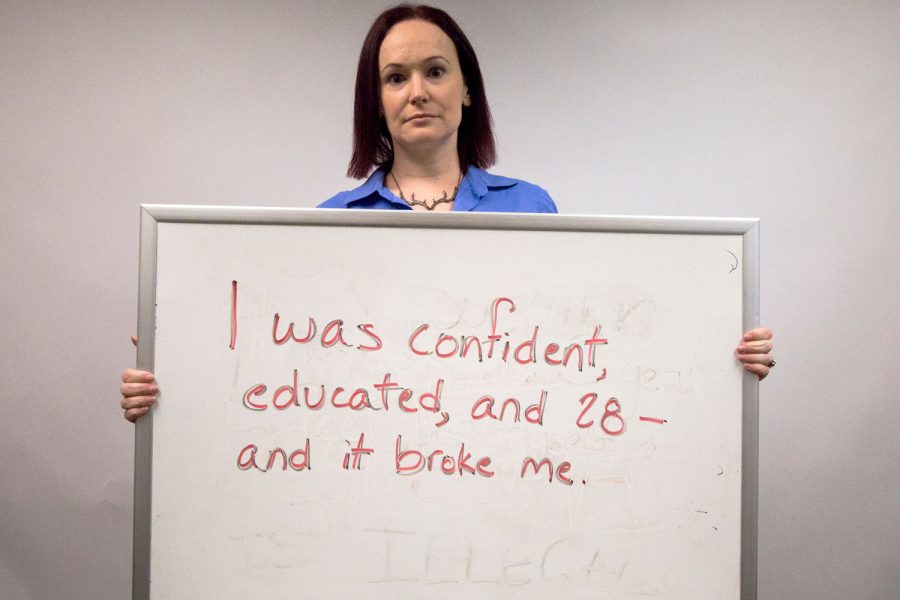

It doesn’t matter how smart you are, or how educated you are, or how confident you are, Morgan said . Sexual assault can break you.

“I was a very well-educated person. I was in a Ph.D. program. I already had a master’s degree, and I was 28,” Morgan said. “Even so, when it happened I felt like I was 5 years old. I felt small and stupid and completely alone and insignificant.”

Morgan said the perpetrator was one of her closest friends, and that made it even more heart-breaking. She said people should understand that if it is someone close to you that assaults you, you will miss them.

She said she wants people to know that it is OK and even normal to still feel the love you have for them. The love doesn’t just go away.

“That’s actually one of the most painful things about the aftermath of it,” Morgan said. “I never talked to him again, but I missed him terribly. He was my friend. I missed his jokes, I missed talking to him. I missed being close to him. And that sucked. But that’s normal. It is not a simple thing.”

Morgan said when she told her partner she was assaulted, he didn’t believe her. He believed it happened,but he did not believe it was sexual assault. She said he went as far as to blame her for it. He asked her the stereotypical questions: What were you wearing? How much did you have to drink?

“He even said to me, ‘What did you think was going to happen?’” Morgan said. “I was more shocked by that than the actual assault itself. This was the person I expected to be on my side.”

One reason she wants to tell her story is to explain to victims that if people do not believe you, do not let that confuse you. She said it confused her greatly when her partner reacted that way.

She began to think that he was right and maybe she deserved it. She began to question if what happened should be considered sexual assault. She wondered if it was all just a misunderstanding.

“It confuses you, and you start to lose faith in your own judgement,” Morgan said. “That was one of the most terrifying parts about being assaulted.”

Morgan said if someone you know has been assaulted and they come to you, it is imperative that you support them. That you listen. That you don’t try to minimize what happened to them.

“It is vitally important that you support them because it does affect what they are going to do and how they are going to look at themselves,” Morgan said.

For three years after her assault, Morgan said she could not wear skirts. Seeing other women in dresses and skirts made her skin crawl. She felt like skirts and dresses left her physically vulnerable. She said she knew these thoughts and feelings were irrational even as she had them.

“It was almost like a self-loathing thing,” Morgan said. “Obviously, it is not the victim’s fault, and nothing you could ever wear will justify sexual assault. Sometimes the anger people feel when they grieve is misdirected. I should have been angry at him … I wasn’t though. I was angry at other victims.”

She said victims need to try not to judge themselves during the healing process. There is no statute of limitations on what you feel or how long you can grieve. She said people will handle the grief in different ways, and not all of them will be rational.

“All of my male friends that I told said the exact same thing,” Morgan said. “They said, ‘Well I’m not surprised,’ or ‘Well you know that guy.’ They were completely not surprised, nonplussed, and unimpressed by the situation.”

Morgan said that horrified her. She wondered why they wouldn’t warn her about “that guy” if they knew he did not respect women. It indicated to her there were conversations between her other guy friends and the perpetrator that she was not privy too. That other women in their lives were not privy to.

“Men need to do more to reign each other in…They need to stand up and say, ‘You know what, let’s not talk about women this way,’” Morgan said. “They need to do that because otherwise they are not going to be surprised when it happens.”

Morgan said the reason why there are so many sexual predators is because they are opportunists. They don’t really plan on taking advantage of women. They are not plotting it out, but if they are given the opportunity they will take it.

Morgan said the reason why is because of the culture. It is because of the way we raise boys, the way we talk about this stuff and blame women. She said it is because the way guys are always getting props for getting laid.

“It’s a problem and we all need to be a part of the solution,” Morgan said. “We need to be better bystanders. We need to be better friends.”

If you hear “locker room” talk, she said you need to squash it. If you see someone trying to take advantage of another person, you need to intervene.

If you are a victim of sexual assault you need to find a support system, she said. You should have somebody to confide in.

Morgan said the assault itself only lasts a few moments. She said that is the easy part, relative to the fall out, relative to what victims must go through emotionally to deal with what they survived.

“In the moment, they can get through anything if they have to,” Morgan said. “But once that moment is over and they actually have to absorb and take in what happened, that’s the work. That’s the hard, hard work. That’s where the resources are absolutely essential.”

Editors’ note: This is the first installment in a series of stories The Horizon is publishing about sexual assault. The next story explores resources available to survivors.