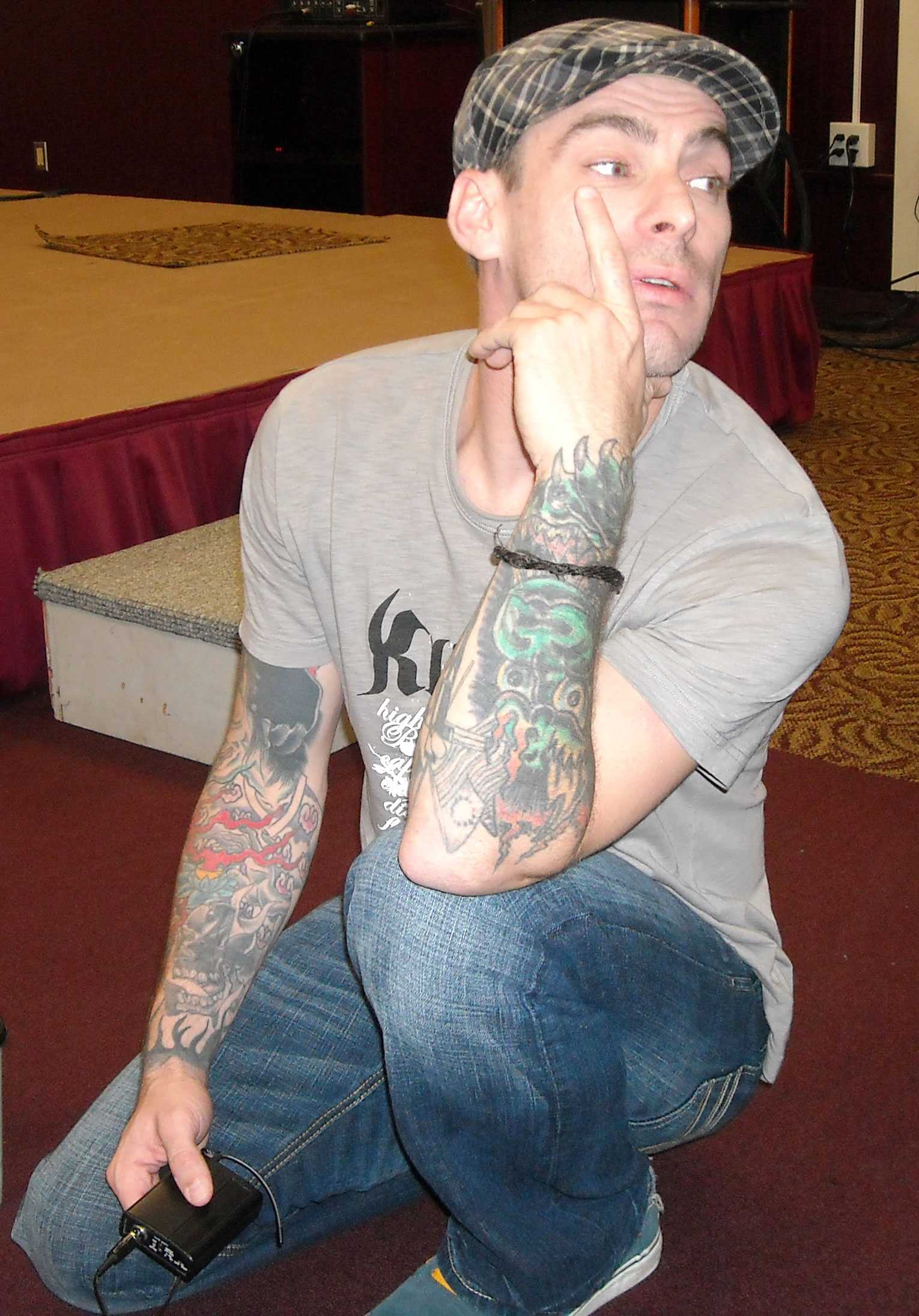

Frank Meeink, author of “Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead,” spoke at IU Southeast on Sept. 29 in the Hoosier Room.

He discussed his life story — from his childhood to becoming a leader in the skinhead community along with his prison experiences.

Meeink began his speech by warning everyone he would curse and possibly offend others’ beliefs of God.

“I am not a professional speaker,” Meeink said. “I am not politically correct. I will speak of a God — not your God — my God. I curse a lot, and I will curse while I talk about God.”

Students said they appreciated his bluntness.

“I must say, Frank was blunt and to the point, which was part of the reason I enjoyed him and his story so much,” Shallon Alford, criminal justice senior, said.

Brian Hostetler, art junior, said he also enjoyed hearing Meeink speak.

“I thought it was cool that he wasn’t like, ‘I changed my ways, so I’m a celebrity,’” Hostetler said. “He was more straight-forward than that. I enjoyed the cussing a lot.”

Meeink said talking about these events is difficult.

“It is emotional,” Meeink said. “That’s why I add some comedy in there to make it funny also.”

He spoke of the child abuse he received frequently by his mother’s live-in boyfriend.

“Every day, I wanted to get hit by a car so I could go to the hospital instead of going home,” Meeink said.

During his middle-school years, Meeink moved in with his dad where he attended Pepper Middle School in Philadelphia.

“The school was 90 percent black kids,” he said. “I went to school hoping I didn’t get in a fist fight each day.”

In 1989, Meeink moved to Lancaster, Pa., where his cousin had posters of Hitler and swastikas on the walls.

“When my cousins’ skinhead buddies would come over, they would say things like ‘multi-racial societies do not work,’” he said. “I was 14. I had no clue what they were talking about.”

Meeink said they would ask him about growing up in south Philadelphia.

“I finally felt like someone asked me how my day was,” he said. “I liked that they asked me about me. No one ever did that before.”

He shared with the audience what made him decide to become a skinhead. After causing trouble at a club, Meeink and his skinhead friends were waiting outside when one of the men he had kicked in the face saw them in the parking lot.

“When he seen us he walked the other way,” he said. “I loved that feeling. I loved seeing the look in his eyes and knowing someone feared me for once.”

Later that night, every one of the skinheads at his cousin’s house took turns shaving a row of hair on his head.

“I had never met a Jew,” he said. “This guy would preach to us and tell us that Catholicism was the biggest Jewish institution, and he would say the Federal Reserve was being run by the Jews. I was told that Eve was impregnated by the serpent and that Kane was that start of the Jewish race.”

From then on, Meeink moved to different states and began recruiting more skinheads for the movement.

“Violence was our whole movement,” he said. “Our greatest ally was the local newspapers. ‘If it bleeds, it reads.’ Newspapers love racism. They referred to me as a leader.”

After kidnapping and beating a young man, Meeink was charged as an adult at the age of 17 with a sentence of three-to-five years.

“They gave us books to read,” he said. “In the Bible, I read about fasting. I was told by the guard if I ate, they would let me out of ‘the hole.’ This is where God proved to me he existed. He gave me what I needed.”

While in prison, Meeink became friends with African-Americans and a Latino.

“I still had my Aryan friends in prison, but I also hung around with my black friends,” Meeink said. “I wasn’t your garden-variety racist. I had beliefs.”

When released from prison, Meeink got a job working in an antique furniture store for a Jewish man, Keith Brookstein.

“He was cool but still Jewish,” Meeink said. “One day, I broke a piece of furniture and called myself stupid. Keith told me how smart I was. I was so thankful for having this human being in my life. I was embarrassed of my beliefs. That was my final day as a skinhead.”

He said he sees the world differently now.

“The only difference between races is one strand of DNA and how close we live to the equator,” he said.

Now Meeink helps children through program he founded — Harmony Through Hockey.

Harmony Through Hockey is a program that helps children ages 6 to 12 in urban areas to accept diversity through team-building — on-and-off the ice.

By KRISTINA BLEUEL

Staff

kcbleuel@umail.iu.edu