WARNING: Learning May Cause Discomfort

A look into the trend triggering debates across college campuses

March 21, 2016

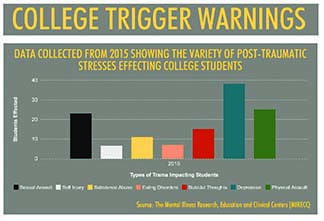

A cultural movement that places a stronger emphasis on the emotional and mental well-being of students emerged at universities across the country in 2015.

A cultural movement that places a stronger emphasis on the emotional and mental well-being of students emerged at universities across the country in 2015.

Students are becoming increasingly aware of causing offense or being offended, and it has changed the way material is being presented to them in class.

A reaction to this awareness has been a rise in the use of trigger warnings, which are meant to caution students of sensitive material that could potentially cause discomfort by triggering memories of past traumas.

A story published in The Atlantic titled “The Coddling of the American Mind” posited that this new sensitivity may have negative consequences for universities, professors and the students at the center of the crusade.

According to the article, students have been filing complaints against professors at a staggering rate.

In response to this, several professors have published articles detailing their experiences.

A professor from Harvard wrote a piece for The New Yorker in which she discussed an incident involving students asking law professors not to teach rape law at the university, and, if they must, to use the word “violate” instead of rape.

The authors claim the aim of the movement is to turn campuses into safe spaces scrubbed “clean of words, ideas, and subjects that might cause discomfort or give offense.”

They refer to the means used to achieve this goal as “vindictive protectiveness,” since those who interfere with the process could be punished with charges of “insensitivity, aggression, or worse.”

According to the article, this new sensitivity could lead to young adults being unprepared for the harsh realities of American society.

On the opposite side of the argument sits those who believe the rise in trigger warnings has given students more freedom in the learning process.

An opinion piece in The New York Times said that, though these warnings should not be mandatory, there is no reason not to issue them to students.

According to the article, the movement is less about coddling students and more about “enabling everyone’s rational engagement.”

According to the article, the movement is less about coddling students and more about “enabling everyone’s rational engagement.”

Diane Reid, senior lecturer in communication studies, said she has been using trigger warnings for years, long before the issue became the hot-button topic it is today.

“When I have used trigger warnings, it has been because of the nature of a specific piece of material that I am using in the class. It might be a particular speech that I am having them read. It might be a video that I am having them watch,” Reid said.

“I mention it the first day of class. I tell them to talk to me if there’s anything that they might find disturbing to the point that’s it’s not just ‘I’m uncomfortable,’ but that your physiological reaction could be debilitating.”

According to The New York Times, trigger warnings originally emerged in online communities to alert those with PTSD of material that depicts common causes of trauma.

Michael Day, professor and personal counselor at IU Southeast, said when he issues trigger warnings they tend to align with the original purpose from their early days on the Internet.

“I use them if we are going to be talking about things like rape, abortion, child neglect and suicide. Things that could potentially trigger the students themselves,” Day said.

“I do it not so much for fear of where the discussion will go, but if someone has experienced something like that before, I want them to be able to emotionally prepare themselves for that discussion.”

Day said giving warnings has proved to be very useful and important to students in many instances.

“Last year, I had a whole class that I taught on suicide,” Day said.

“I had a woman come up to me and tell me that she had a son who took his own life two months ago, and she really didn’t feel like she could sit through it.”

Reid said these warnings are similarly useful for students who have previously served in the military.

“If I know I’ve got a vet with wartime experience in there, there might happen to be noises that would set them off in a film. I know from having worked with vets in the past. My son is in the military, and so is my daughter-in-law,” Reid said.

“You have to be knowledgeable as a faculty member about whether something like that might be a trigger.”

Day said that, though trigger warnings are appropriate at a certain level, he does not want to get into a situation where certain topics have to be avoided in class.

He said that, while he continues to issue the warnings to undergraduates, he avoids using them with his graduate students.

“The reality is that they are going to be walking into a room with a client. You don’t know what that client is going to give you,” Day said.

“You have got to be able to handle your emotions. That’s a crucial skill. I think in certain disciplines, part of your training needs to be that you need to be able to manage yourself no matter what’s coming at you. It’s true for just about any professional when you really think about it.”

Reid said she has heard a variety of objections to material during her career, including instances where students were uncomfortable with curse words used in literature.

In response to complaints such as these, Reid said she has had to learn to differentiate between the varying levels of severity of student objections.

“In cases where it’s a matter of discomfort, I’m not much of a coddler. I’ll say ‘folks this is not pretty, but this is reality.’ There’s this protect versus challenge debate going on with the trigger warnings. If someone is just uncomfortable, I’m a realist,” Reid said.

“We’re going to encounter a lot these things. They’re not pretty and you may be uncomfortable for the time being, but the idea is for you to ultimately think about this and what it means.”

Though Day believes trigger warnings are important in instances where serious trauma is involved, he said an oversensitivity to other issues could have a negative effect on the learning process.

“Some faculty may choose to not address certain issues because of their lack of comfort in dealing with what might come at them. They just don’t want to deal with it, so they might water down or completely avoid topics,” Day said.

“You miss so much, especially in literature. There’s so much material in literature that’s very challenging. It’s part of the human condition. We can’t put our head in the sand and believe that th ese things don’t exist out there.”

ese things don’t exist out there.”

Day said the Internet and social media have allowed students to share their opinions more easily than ever before.

Despite this, he does not believe professors should overreact to this heightened social awareness by changing their teaching methods.

“At the university, what we are supposed to be about is having a diversity of voices. If you only get to hear one voice, are you really getting a good education? If I’m only teaching you one side, I’m really doing you a disservice,” Day said.

“We need to hear these things. We’re not idealizing any particular message just because we’re putting it in your face. We’re exposing it to you and letting you look at it so you can decide what’s good in it and what’s not good in it.”