He is the clever politician, lying and deceiving to reach the top of the food chain. He is the crazed drug lord, destroying all those who get in the way of his goals. He is the philandering businessman, intent on satisfying his own wants at all costs. He is the antihero, and television audiences are fascinated by him.

Antiheroes, unlike traditional protagonists, do not always make noble and righteous choices. During the course of their shows they often lie, steal, and destroy for personal goals and desires. Walter White (“Breaking Bad”), Frank Underwood (“House of Cards”), and Don Draper (“Mad Men”) are central characters in their respective shows with deep, moral conflicts.

Each protagonist is shown to have likable characteristics while performing immoral—or downright evil—deeds. Their complex moral codes and appalling actions have attracted millions of viewers over the past few years.

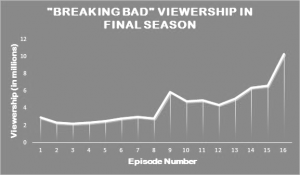

According to Nielsen ratings, 10.3 million people watched the “Breaking Bad” series finale last fall. The series also topped Nielsen’s 2013 Twitter TV ratings with an average of six million people reading tweets about each episode.

Likewise, the Netflix hit “House of Cards,” which focuses on the rise of a corrupt, deceitful politician, has seen national success. According to broadband analysis company Procera Networks, about two percent of all U.S. Netflix subscribers binge-watched the entire second season of “House of Cards” within the first weekend of its release.

Michael Jackman, senior lecturer of English, said antiheroes may be appealing to viewers because they can relate to them on a basic level.

“Antiheroes, I imagine, become popular when there is a strong feeling of dissatisfaction with the mainstream,” Jackman said. “We root for the underdog, often isolated and alienated, to the extent we all feel like underdogs.”

Danielle Willoughby, psychology senior and avid “Breaking Bad” fan, said rooting for the underdog was an important reason why she appreciated the Walter White character.

“He’s a high school chemistry teacher that everyone underestimated,” Willoughby said. “He does whatever he has to for his family.”

Jackman said this soft spot for his family makes White particularly relatable for the viewers.

“Why, he’s just a schmo facing a terminal disease who wants to do what we all do – provide for our families,” Jackman said.

During the course of “Breaking Bad,” White transforms physically and mentally. In the first episode, he discovers he has terminal cancer. The fear of leaving his family with little money pushes him to make and sell meth.

As the series progresses, White remorselessly lies, betrays and murders his way to power to provide for his family.

Willoughby, who has seen every episode of “Breaking Bad,” said White’s journey from mild-mannered chemistry teacher to ruthless drug lord is also an emotional journey for the viewer.

“You really grow with him during his experiences,” Willoughby said.

Noah Bailey, elementary education junior, said Frank Underwood, the antihero politician in Netflix’s “House of Cards,” is likable for his brutal honesty.

“He tells you what he really feels. He’s upfront to the audience about everything,” Bailey said.

During the course of his show, Underwood schemes, deceives, and backstabs to exact revenge on those who wronged him. Bailey, who watched all 13 hours of the second season of “House of Cards” the first day it was released, said he respects the man despite his evil deeds.

“He passes bills by backstabbing others,” Bailey said. “But he actually gets things done.”

Unlike the strict moral guidelines of traditional heroes, antiheroes like Walter White, Frank Underwood and Don Draper make choices that are unpredictable, relatable and believable.

Although their actions are appalling at times, viewers want to see antiheroes succeed because of this emotional connection they develop with them.

Jackman said this moral ambiguity allows the viewer to glimpse beyond our society’s mainstream values, which gives the antihero a power the traditional hero lacks.

“Because an antihero is antagonistic to those mainstream values, that character is allowed to say things and observe things that a character in the position of the hero can’t,” Jackman said. “So through an antihero we can get a social critique of the mainstream.”