Louisville photographer makes photos by hand

Rudy Salgado uses 1850s tintype technique to connect with the history of photography

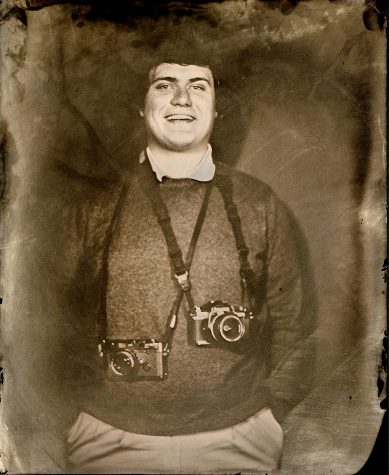

Rudy Salgado stands in his darkroom, a repurposed closet dimly lit with an orange safelight. In this small space, Salgado prepares and develops his tintype photos.

January 12, 2020

For Rudy Salgado, Instagram filters are just not enough. A Louisville, Ky.-based artist passionate about creating art with his hands, Salgado decided to make his photographs look ‘old-fashioned’ by making them the ‘old-fashioned’ way.

He uses the tintype method, a photographic technology invented in the 1850s.

“I’d call myself a tintypist before I’d call myself a photographer,” Salgado said. His artistic background is printmaking, specifically making lithographs on special materials like stone.

He said compared to lithography, tintype photography is a quick process. “It’s a 10-minute photo, but that litho over there took over a year to make,” he said, pointing to a corner of his studio.

account, River City Tintype. Pope said he was excited to have his tintype taken and to support a creative local artist. Photo by John Clere.

Salgado operates the Calliope Arts studio in Louisville with his wife, Susanna Crum, who is an assistant professor of fine arts and printmaking at IU Southeast. The studio is a space where members can use large and expensive printmaking equipment they might not otherwise have access to.

“Rudy and I both really believe in helping visual artists be visual artists. They don’t have to have it as a ‘plan b,’” Crum said. “Having a place to connect with your art and keep going and connect with other people is so crucial because then you remain committed to it.”

Crum said after she graduated from Cornell University, she looked for community studios like the one she now operates. She found one in Chicago, and while there she used the space and equipment to create the work she used to apply to graduate school.

Not a Reenactor

“I’m not a reenactor,” Salgado said. “A lot of tintype people are reenactors, but I don’t want to do that.” He said his piercings and gauges might look out of place at an 1800s historical reenactment.

But history, he said, is one of his favorite reasons to shoot tintypes.

“I feel connected through this process to history,” he said. “Being able to look at tintypes from the Civil War – understanding that process and knowing how it was made – and then imagining these men, mostly in horse-drawn carriages, just going from one battlefield to another to photograph bodies… that was the first time people saw photos from the war.”

Salgado’s love for tintype photography, he said, comes from his desire to handmake his art.

“I think I just love things that are made with the hand, and the time that it takes to make things,” he said.

“I think a lot of it has to do with my relationship with technology. I was born in ‘81, and I graduated high school in ‘99. So I’m one of the last generations that didn’t have cell phones in high school. Right after high school cell phones became pretty popular. We had pagers. I had a fake pager in my pocket that wasn’t hooked up, but it made me look cool.”

Tintype Process

Tintype photography is a completely manual process – the photographer begins with only a camera, a blackened metal plate, and the chemicals needed to make the light-sensitive emulsion coating the plate.

The light-sensitive chemicals, though, are only sensitive to light while they are still wet. This gives the photographer about 10 minutes to take and develop the photo after sensitizing the metal plate before the chemicals dry.

An average tintype plate is significantly less sensitive to light than standard photographic film, meaning a photographer must either expose the subject with an incredible amount of light, or keep the camera’s shutter open for minutes at a time.

Salgado uses bright strobe lights to capture subjects in his studio, but when he is taking photos in the field, such as during one of his pop-up studios at a local bar, he sometimes only has access to natural light. Exposures take minutes at a time in direct sunlight, so subjects must remain very still.

Children, he said, have trouble staying still during multi-minute exposures. Original 1800s tintypes, he said, usually show blurry children when they move during the exposure. “They look historically accurate, though,” he said, “like blurred children ghosts.”

The tintype process begins in Salgado’s darkroom, where he coats a sheet of blackened aluminum with collodion and then submerges the sheet in a silver nitrate bath. The silver makes the plate sensitive to light, meaning a photo can be exposed on it.

Because tintypes are not very sensitive to light, Salgado works in his darkroom with an orange safelight. Tintypes are only sensitive to blue light, meaning red or orange light will not ‘fog’ them. He invites his clients to watch him coat the plate with the chemistry he mixes. Showing clients the process, he said, is one of the most rewarding parts of the job.

“Making tintypes is really cool,” he said. “Interacting with people, showing them the process – especially talking with kids about it, because they’re so used to [smart phones], and then explaining to them, ‘look, you were not still. Look how blurry you are.’”

Salgado uses a 4×5 studio camera for his tintypes, meaning each finished tintype is four by five inches. The camera is heavy and rests on a sturdy tripod.

After focusing the camera’s ground glass under a dark cloth, Salgado triggered a brilliant flash of light and rushed the now exposed photo back to the darkroom, where he developed the photo in front of his clients.

The last step of the photo, called fixing, removes the unexposed silver from the image, making the photo visible. Fixing a tintype can be done outside the darkroom, so Salgado took his clients into the well-lit studio and poured fixer over the photo, revealing it almost instantly as the excess silver washed away. Miranda Post, one of Salgado’s clients, excitedly filmed the event with her phone.

After fixing and rinsing the photo, Salgado seals it. By doing so, he ensures the photo will last forever, given it is properly stored and displayed.

“The original tintypes from the 1860s are still in really good shape,” he said. “Once you finish your plate, you have exposed silver, which is your photograph. If you don’t coat or treat it somehow, that coating will oxidize. Historically, people would use a sandarac varnish, but I haven’t been doing that. I’ve been using an archival wax. I’m in the process of learning how to use the varnish. It’s a little tricky, just because there are so many damn dust particles in the air, so you always end up with little dust spots on your plates. I have to invest in a better filtration system.”

After the photo is sealed, he numbers the backside. “I keep track of all my plates, I number them all. Today’s plate was number 382.”

Salgado’s studio can be found at www.calliope-arts.com.