Brown co-credited for creating celebration

The high-five is one of the most iconic, dynamic and yet simple of social gestures. In the past four decades it has become an unmistakable thread in our cultural fabric and traveled the world over.

Even recently, the popularity of the high-five has manifested into an unofficial national holiday. Five students from the University of Virginia created “National High-Five Day” in 2002. Soon after, the students formed the ‘National High-Five Project,’ which is a charity that funds cancer research nationwide.

Though the impact of the high-five is unquestioned, the origins of the gesture remain a mystery to this day.

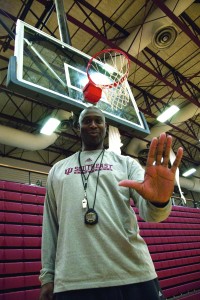

ESPN has narrowed the invention of the high-five to two athletes in different years on opposite sides of the country. Many believe it was either Glen Burke of the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1977 or Wiley Brown, IUS men’s head basketball coach, and Derek Smith of the University of Louisville basketball team in 1980.

Since Glen Burke and Derek Smith are deceased, Wiley Brown is one of the last living links to the high-five’s origins.

Brown and Smith, two of the self-titled ‘Doctors of Dunk,’ were members of the 1980 University of Louisville NCAA championship team.

Brown said he can still remember the day he and Smith high-fived for the first time.

“We use to do low fives in practice all the time,” Brown said. “But one day in practice, my best friend, Derek Smith, said, ‘Give it up high.’”

Brown said both of them being tall is one thing that helped them with in the creation of the move.

“You got to understand, you’re talking about a 6-8 guy and another 6-8 guy,” Brown said. “Why are we going to do low fives, so we just threw it up high, and that’s how it happened.”

“It was a wild moment,” Brown said, “because no one had been doing it. We really had a knack for starting things and turning them into a phenomenon. I’ll never forget that team. They are still a really unique group today.”

Kathy Tronzo, University of Louisville program assistant for sports information, worked for the University of Louisville Athletics Department during the 1980 basketball season.

“It was a very exciting time,” Tronzo said. “I watched every single game and even went to the NCAA championship game in Indianapolis.”

Tronzo said she remembers the new presence of the high-five during that season.

“They were always so fired up,” Tronzo said. “I think the high-five made them closer as a unit which is important in a championship.”

Tronzo said the team’s bus was mobbed by fans upon return to campus from Indianapolis after the university’s first NCAA championship win.

“All the students surrounded them and the team couldn’t even get off the bus,” Tronzo said. “The students were cheering and dancing around.”

Brown said he remembers that night vividly.

“They were climbing up on top of the bus, almost caving it in,” Brown said. “When we got off there were high-fives all around. We were like rockstars.”

“That first win was special,” Brown said. “And it’s still special today.”

“We had lots of games that were nationally televised,” Brown said. “After a while we noticed other teams started doing [the high-five] too. It was something that caught on throughout the nation.”

Brown said he only recently heard of the claim that Glen Burke may have also invented the high-five.

“I’ve never disputed it,” Brown said. “More power to him — I just know from my end, we started it and from there it became a phenomenon.”

A third possible candidate for the high-five’s invention was short-lived. Originally, the National High-Five Project claimed that Lamont Sleets, a basketball player for Murray State University, had invented the high-five.

Greg Harrell-Edge, executive director of the National High-Five Project, said the credibility of their organization came into question when a reporter for ESPN followed up on the Lamont Sleets story last year. Harrell-Edge said the organization admitted they had fabricated the story when they were contacted by the reporter.

“We got into a bit of hot water over the story,” Harrell-Edge said. “We kept getting asked who invented the high-five, so my buddy just made up this story so people would stop asking us. “

Harrell-Edge said the organization learned of the Brown and Burke stories years later.

“We felt really bad that we had tip toed on the legacy of these folks,” Harrell-Edge said. “And we wanted to make good with them.”

Harrell-Edge said the organization reached out to the families of Smith and Burke and coordinated fundraisers in honor of their legacy.

Though Brown was not aware of the controversy, he said supports the charity’s efforts.

“We all know somebody who is touched by [cancer],” Brown said. “That’s a great thing to raise money for. I’m behind that 100 percent. That puts a big smile on my face.”

Brown, who is now the men’s basketball head coach at Indiana University Southeast, said he is proud of his legacy in connection to high-five’s invention.

“I tell my players about it,” Brown said, “because I want them to know about the impact I’ve had on the game, and that they can leave their own legacy also.”

Keagan Clark, junior forward, said Brown told him about the high-five story last season.

“At first I thought it was a joke,” Clark said. “And then he started going into the story about it, and it was really cool. I think he should get some kind of award for it.”

Brown said he smiles when he sees athletes still giving high-fives.

“It’s a unique part of the game,” Brown said. “It’s part of history and I’m very proud of it. I talk about it, smile about it and marvel over it every day. It’s a great story.”

By SAM WEBER

Staff

samweber@ius.edu