Waiting to Welcome

Members of the IU Southeast community share their thoughts and experiences about the refugee travel ban.

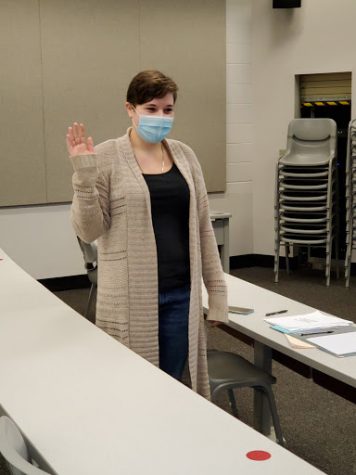

Members of the Kentuckiana community gather at the Louisville International Airport on Friday, Feb. 3, to welcome the last refugees into the city before a temporary shutdown of refugee admissions begins.

IU Southeast alumnus Sadiq Mohamed was 20 years old when he first came to the United States from Somalia by way of a refugee camp in Kenya.

“I knew that I wanted a better life, I knew that if I do get to come to America then that will open doors that will have more opportunities to have a better life,” Mohamed said.

Mohamed’s mother came to the U.S. a year ago, and he was in the process of bringing his brothers to the country. Then President Donald Trump signed an executive order that at least temporarily halted his plans.

The order, signed on Jan. 27, halted immigration from seven predominantly Muslim countries, including Somalia, cancelled all refugee settlement in the United States for 120 days and indefinitely suspended refugees from Syria. Trump also reduced by more than half the number of refugees allowed into the U.S. this year. Trump said this is to allow time to implement new screening procedures.

Now, Mohamed and his family wait, afraid of what will happen next.

“With this hold, now everything’s suspended,” Mohamed said. “My mom is horrified, and she’s scared. She doesn’t know what to do. She wants to go back and just be with them because she doesn’t know the outcome of how things are going to end up being, and that’s the the most scary part. Nobody knows what [Trump’s] going to do next.”

Who are the refugees?

Lisa Hoffman, assistant professor of education, is on the board of Kentucky Refugee Ministries. She said many people are confused about who refugees are and how they are different from other immigrants. She said refugees are not illegal immigrants. And in fact, there are two separate executive orders signed recently: one regarding illegal immigration and the border wall, and the other regarding travel restrictions and a refugee ban.

“The wording of [the executive order] talks about it relating to security. However, one thing people should know is that refugees go through more vetting and more stringent security checks than any other category of immigrants to the U.S.,” Hoffman said. “It usually takes at least two years for a refugee to pass all the checks to get clearance to come.”

Hoffman has worked with Kentucky Refugee Ministries for more than a decade training their tutors and mentors, as well as teaching English.

“Refugees can be absolutely like you and me,” Hoffman said. “So when someone comes in as a refugee, they could be like an uneducated, oppressed person who’s always lived in poverty. But they could also be a doctor, a lawyer, a professor.”

According to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services under the United States law, refugees are defined as someone who:

- Is located outside of the United States

- Is of special humanitarian concern to the United States

- Demonstrates that they were persecuted or fear persecution due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group

- Is not firmly resettled in another country

- Is admissible to the United States

- A refugee does not include anyone who ordered, incited, assisted or otherwise participated in the persecution of any person on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion

Omar Attum, associate professor of biology, lived in Jordan for two years on a Fulbright fellowship. More than a third of the country’s population is made up of refugees, according to a World Bank official. This allowed Attum and his family to live among refugees and understand them and their struggles.

“They live under this shadow of uncertainty, because they are vulnerable in terms of their legal status potentially,” Attum said.

Attum said Jordan is the most water-starved country in the world, and that it’s also significantly poor. These issues aside, the country still welcomes refugees and has lower crime rates than most major metropolitan cities in the U.S.

The local refugee community

Louisville has been accepting refugees for several generations. According to the Kentucky Office of Refugees, 18,822 refugees from 53 countries have been resettled in Louisville since 1993.

“Refugees have really contributed a lot to our local culture,” Hoffman said. “There are some neighborhoods in Louisville that have been revitalized because of an influx of new families there that open new businesses.”

Tatum Tedtman, psychology senior, volunteers at Catholic Charities, one of the two organizations in Kentucky working to resettle refugees in the state.

“They fill some of the jobs that we need filled,” Tedtman said. “There are refugees out there who are doctors here, professors, researchers. And without them we would severely lack in a lot of different ways.”

KRM and Catholic Charities, the two major resettlement agencies in Kentucky, provide a great deal of services to refugees to help get them get settled and become self-sufficient.

Between the two organizations, their services include teaching English classes, helping with job placement, providing cultural orientation for refugees to learn social norms in the U.S., helping find medical services if needed, and teaching refugees about over-the-counter drugs and how to ride the bus.

The organizations have opportunities for kids to get matched up with tutors or mentors, as well as provide caseworkers to help navigate issues such as a difficult landlord and immigration lawyers in case there are legal problems.

The organizations will also pick refugees up from the airport, get them settled into an apartment, provide them with furniture and pay their rent for their first eight months in the U.S., or until they get a job.

Among all refugees, Kentucky last year took in more than double the national average of refugees per 100,000 residents.

Mohamed said on average, Catholic Charities will resettle 40 refugees each week. According to Hoffman, KRM resettled 874 in Louisville and Lexington last year. This year they were scheduled to get 680 before the executive order halted that. On Feb. 3, the city of Louisville received their last refugee for resettlement for the next 120 days.

Mohamed works as a self-sufficiency caseworker at Catholic Charities. His job involves getting clients to be self-sufficient and eliminating barriers to reaching that point.

Mohamed told the story of a client of Catholic Charities who’s a single father with a disabled 18-year-old son.

“It’s a miracle he’s still alive,” Mohamed said. “His condition is critical, and the father was in the process of getting his family over here to at least see him before he dies. All he wants is to see his mother one last time. [He] will probably die without seeing his mother because of the executive order.”

Mohamed isn’t the only one with concerns for the future.

“I’m waiting for the time to happen where it’s going to escalate,” said Mark Jallayu, political science junior and Student Government Association president.

Jallayu came to the U.S. as a refugee in 2006 with his family. His parents fled from a civil war in Liberia, which led to Jallayu’s birth in a refugee camp in the Ivory Coast.

When asked about his reaction to the executive order, he said it was hurtful.

“It makes everything inside hurt because there’s a great humanitarian crisis going on in those countries, and to just close the doors in those countries because we’re scared,” Jallayu said. “This is not the America I know, this is not the America I knew back home. A place that welcomed people.”

How to help

KRM and Catholic Charities are always in need of volunteers and donations. Volunteers can assist in teaching refugees how to speak English, how to ride the TARC and more.

“I definitely urge young people to get in the mix of these things and to get out there and rally and vote,” Tedtman said. “You have to stand up for people whose voices have been silenced. Writing letters to our representatives.”

Jallayu said he’s in a unique time as SGA president, and because of that he can’t stay neutral regarding this issue.

“I have to take a stance, and my stance is that every person belongs, whether you’re a refugee or not, you belong,” Jallayu said.

Jallayu said he was grateful to be representing the student body.

“I’d like to see us do more than protesting, I want to see us reach out to our representatives,” Jallayu said. “We need to call our representatives in Congress and at the state level to make sure that President Trump is accountable, but at the same time we need to work with the ACLU that has been thinking about the lawsuits to make sure that President Trump is accountable.”

Both Indiana University President Michael McRobbie and IU Southeast Chancellor Ray Wallace sent out e-mails to the campus community expressing support for students and explaining that the recent executive order goes against IU core values.

Attum is upset about the executive order, finding it absurd that the U.S. is shutting out immigrants and refugees when those are the type of people who built our country.

“Even the founding fathers were refugees from religious persecution,” Attum said.

Attum said he feels the recent ban is due to fear.

“A lot of it is just fear mongering, praying upon people’s fears of the outside and the unknown,” Attum said. “We shouldn’t fear refugees. We should welcome them.”