Border Battles

Diving deeper into the biases behind residents of Louisville and Southern Indiana

Todd Manson, IU Southeast associate professor of psychology, frequently uses the biases which both New Albany and Louisville residents place on one another as an example in his class.

Assumptions about both sides of the Ohio River have been made for years, going as far as creating a fear of driving from one side to the other for some individuals.

“It’s a classic case of what we call ingroup bias,” Manson said. “So the explanation of that would be ‘us versus them’ thinking.”

Ingroup biases, meaning an individual’s perception of their ‘group’ — or in this case, their town — is viewed as better than the other and “going along with negative stereotyping” as explained by Manson.

From genocides in South Sudan, to battles between favorite teams, humans naturally and easily make stereotypes about others in order to make the individual feel at ease about their current state of being.

In the case of border battles between southern Indiana and Louisville, tendencies to assume one side has a hopelessly increasing crime rate while the other has more advantages in their public school system are common among residents.

“Growing up, I always thought more schools from Louisville would beat schools from New Albany just based on how many more people live on [the Louisville side] of the river,” Kyle Goodman, business marketing senior, said.

While New Albany’s total population is six percent of Louisville’s, the Derby City and one of southern Indiana’s most attractive towns are separated by a river roughly a mile wide, sharing a climate full of allergies and unforgiving humidity.

Both sides have an air quality rating of nearly 51 out of 100, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and a better unemployment rate of 4.8 percent compared to the rest of the country’s 5.2 percent average.

Although some of the stereotyping of each city by the other’s residents has created socio-economic thoughts for debate, legitimate intentions can often be blended with the hopes of enhancing one’s self-image.

“A couple of main motivations that we know in social cognitions and how we think about other people is that if something saves time and effort, people will use that,” Manson said. “So stereotyping saves time.”

From the Beginning

Human nature has evolved to stereotype groups of others and has done so for its entire history, though influences can commonly play a part in the overall thought process of individuals starting at a young age.

It isn’t until the youngest generation is exposed to the diversity of the world that the children truly understand just how similar they are to other races, sexes and religions. Until then, the natural reaction is to think only of differences.

“I think you’d have to be around people or encouraged by parents, teachers or peers to not think that way,” Manson said.

By the time the youth has developed a grasp of what stereotyping is — though not necessarily understanding such terminology nor inaccuracy in their assumptions — certain beliefs about Indiana and Kentucky begin to enter the mind.

“Indiana is only good for corn and basketball,” or “Kentuckians only date their cousins,” are common stereotypes that are implanted into children’s thoughts from an early age throughout Kentuckiana and beyond.

“I never even went across the river as a kid,” Goodman said. “If I did, it was to go to Huber’s Farm or maybe baseball. Other than that, I didn’t really have a reason to [go].”

Beyond the development of biases between the two cities and states, humans have evolved to stereotype situations that might involve danger.

The fight-or-flight response from hearing a growling wolf or seeing a snake in the grass can be attributed to stereotyping these dangerous situations. The same process has become evident at a social level as well.

“Most of human history involved groups of African people in the Savannah fighting for survival,” Manson said. “So maybe that’s a reason why we’ve evolved to seeing others as good and bad.”

Business Benefits

Though the biases residents of both cities make, there are plenty of business opportunities in an expanding metropolitan area which Louisville mayor Greg Fischer addressed in a commentary on Insider Louisville.

With his intentions being on an improved air service, Mayor Fischer also mentions opportunities in both New Albany and Louisville can benefit from through a scheme known as the Bluegrass Economic Advancement Movement (BEAM).

“All of those infrastructures and developments in the local area will certainly be attractive to people in general,” Kathleen Arano, IU Southeast associate professor of economics, said. “Now, how much importance you place on these amenities depends on the individual.”

Fears of driving to one side of the river or the other and getting lost are understandable, though some of the stereotypes that ultimately hold individuals back from making the commute are invalid.

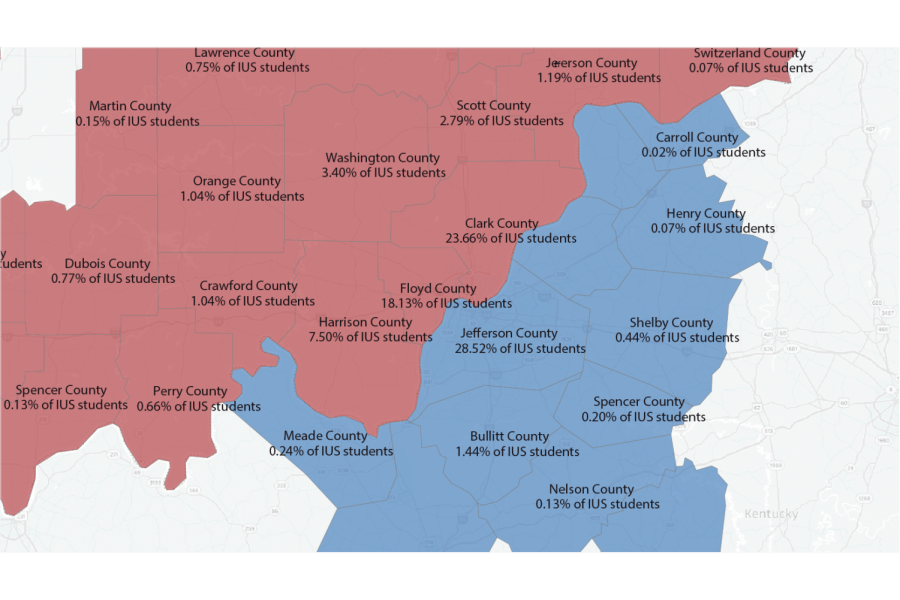

Being one of the only schools with high a number of commuters in the region, IU Southeast itself has benefitted from the closeness of Louisville with 93 percent of its students living off campus.

“It’s unique because we do belong to the same metropolitan area, so in that context [biases] are not a big issue because people here are mobile,” Arano said.

Arano is one of many employed by or who attend IU Southeast while also living in Louisville. She says not only does the school benefit from being in Kentuckiana, but Louisville has seen benefits as well.

“IUS benefits from being in the metropolitan area because there’s a greater pool of students to attract from,” Arano said. “There’s a specific type of groups and services that are needed for this demographic group. It raises the overall labor pool again.”

With the two river cities planning advancements which will be mutually beneficial, IU Southeast will have opportunities to expand as well.

In the meantime, biases that have settled in the minds of residents from both sides remain extraneous to future plans of expansion for IU Southeast and the rest of the metropolitan.