Refugees from crisis-stricken countries like Haiti, Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, DR Congo, and countless others have sought asylum in the United States. And for some, like Sebastien Philippe, their fresh start has taken place right here in the Louisville Metro area.

A total of 45.2 million people have been forcibly displaced from their homes by conflict or persecution, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency. Out of those millions, 70,400 applied for asylum in the United States last year. Some, like Philippe, ended up here in Kentuckiana.

“People probably expect you to be like the sad immigrant from Africa who always gets picked on,” Philippe said, “but not everyone is like this.”

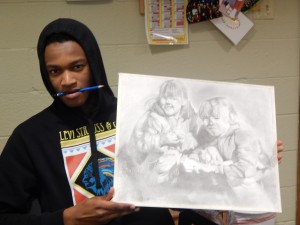

Philippe is the self-described “phone guy” at the Americana Community Center, as well as a working artist doing commissions with the hope of having his own gallery in the near future. He moved to the United States from Cap-Haïtien, Haiti, when he was only 9 years old.

“My father was a pastor who traveled all around the islands of the Caribbean and America so he was the first to immigrate, then me and my family came shortly after,” Phillippe said.

Most refugees who apply for asylum go through long waiting periods and a lot of red tape. Once accepted through the Federal Office of Refugee Resettlement, they are flown to the United States and resettled into their new city. Philippe said he found the experience relatively easy.

“The hardest part was learning English, but I grew up with other Haitian kids who were born here, so that helped a lot,” Philippe said.

But for many immigrating to this country, the transition can be difficult, Allison Smithkier, family center coordinator at Kentucky Refugee Ministries, said.

“Every case varies. We have seen many successes, but it’s always hard,” Smithkier said. “Many initial highs of moving to a new place followed by lows from missing their homelands.”

But organizations like Catholic Charities of Louisville and the Kentucky Refugee Ministries do what they can to ease the growing pains.

“They’re met by a local family who will have a warm meal waiting for them, then they are taken to their new living space that will have everything they need and food in the fridge,” Smithkier said. “And they’re given about $925 in resettlement money.”

Once the refugees arrive in the United States, organizations such as Kentucky Refugee Ministries teach refugees the sometimes rudimentary skills needed to survive in our society.

“Some hold multiple master’s degrees and some don’t know how to write or spell in their own language,” Smithkier said. “We have to teach some how to hold a pencil.”

And for those refugees who have undergone traumatic experiences, the problems of integration are only compounded.

“They’ve already passed a huge milestone leaving their country and getting here, and then it’s another milestone to enculturate themselves, find jobs, and build new lives,” said Angela Cao, patient coordinator at the Survivors of Torture Recovery Center.

Cao said that the torture victims she works with are only a small subset of all refugees, but she said it is one of the most important subsets. She said it is hard to say just how many refugees are victims of torture because the center receives patients based on referrals or self-referrals.

There are primary victims, those who have experienced direct violence, and secondary victims, those who have witnessed it. Secondary victims are usually children and women who were forced to witness torture as a means of intimidation.

“We provide both physician and psychiatric care,” Cao said.

Cao said physicians are on hand because some victims have lasting disabilities due to their torture, as well as high blood pressure and other stress-related ailments.

“It’s harder to measure success because if it were a rash, you would prescribe some cream and you would have concrete evidence that things are improving. This isn’t as clear cut,” Cao said.

For many refugees, even after they have made Louisville their new home and immersed themselves in the culture and community, they are still deeply affected by events in their homeland. Philippe said he can still remember the profound effect the 2010 earthquake in Haiti had on him.

“Imagine all of Louisville just crumbling, falling apart,” Philippe said.

He said would hear stories from family and friends of entire buildings falling on families. And even though he has spent most of his life in America, Philippe said he still grieved for his homeland.

One day he hopes to return, but Philippe said he is satisfied for now.

“I am just living life, everything is good,” Philippe said. “I’d like to visit some family I have in Philadelphia and New York. And I really want to see the MoMA [Museum of Modern Art].”